DIAMOND EMPOWERMENT:

THE ZIMBABWE CASE STUDY

“Diamond Empowerment” is a series of articles, each one a case study, providing an objective overview of the contribution – both realized and still only potential – that the diamond mining industry makes to sustainable development in the African countries where it is present.

The first looks at the Republic of Zimbabwe, which is scheduled to become the Chair of the Kimberley Process at the start of 2023. The country currently serves as the KP Vice Chair.

Compared to its southern neighbors, Botswana and South Africa, Zimbabwe was a late comer to the diamond mining industry. Although alluvial deposits were first discovered in its territory as far back as 1903, it was only in 1997 that geologists working for the Australian mining giant Rio Tinto uncovered a series of kimberlite pipes near the town of Zvishavane in the southeast of the country. This resulted in the development of the modestly sized Murowa Mine, which came on stream in 2004.

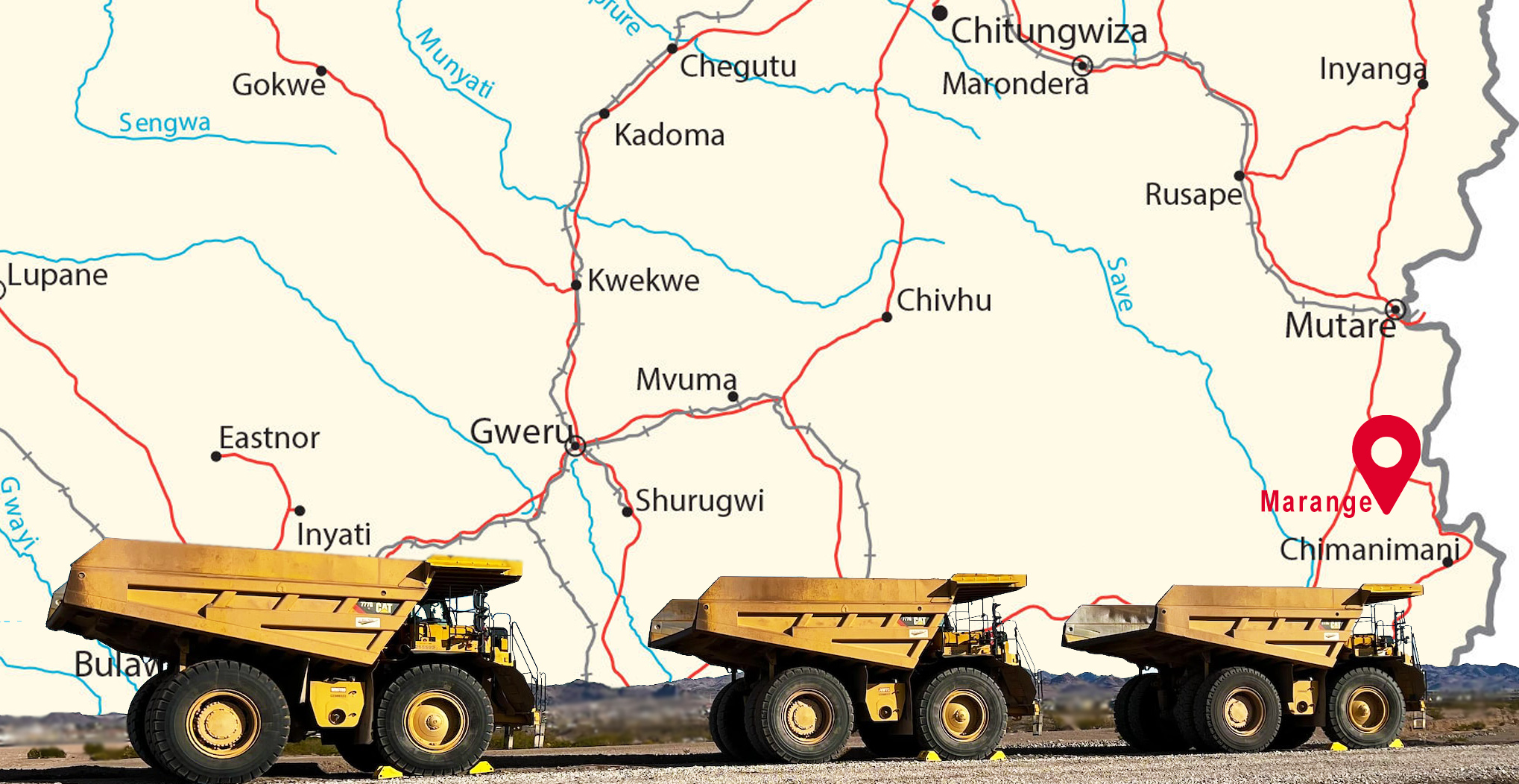

What changed everything, however, was the discovery in June 2006 of massive alluvial deposits in Marange, in the Chiadzwa district near the Zimbabwe/Mozambique border. A British-owned company, African Consolidated Resources (ACR), managed to obtain exclusive rights to the fields.

But, despite its promise, for more than a decade Marange failed to provide Zimbabwe with the substantial developmental windfall that it potentially could have. It became a cautionary tale of power politics, poor government and corporate governance, violent suppression and systemic corruption. Today, however, the alluvial diamond fields also offer the possibility of redemption and hope.

A state of turmoil

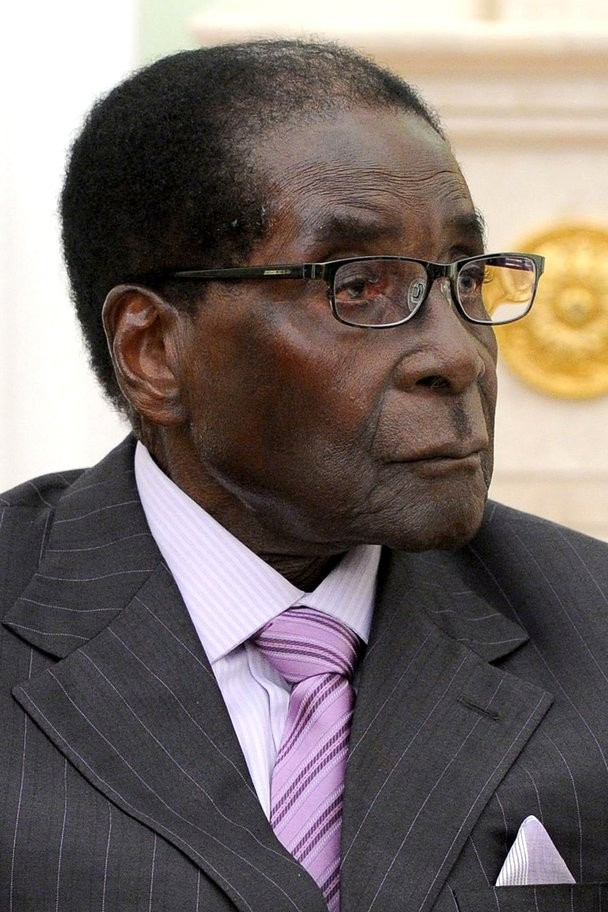

Zimbabwe in 2006 was in a state of prolonged economic turmoil, exacerbated by the populist policies of its autocratic head of state, Robert Mugabe, who had served as president since the country achieved independence in 1980.

Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe’s president between 1987 and 2017.

When his government received estimates that the newly found deposit at Marange may contain reserves worth as much as $800 billion, it revoked ACR’s license and opened the diamond fields to unlicensed miners. An uncontrolled diamond rush followed.

Reports soon surfaced about Zimbabwean police exploiting the miners, both economically and physically, including arbitrary arrests and detentions. Syndicates were allegedly being established to collect bribes. Smuggling became evident. Most was taking place through Mozambique, which was a non-diamond producer and not a KP Participant.

In the summer of 2007, however, it appeared that that the situation was being brought under control. But then, during the latter part of 2008, tens of thousands of artisanal miners returned to Marange.

On October 27, 2008, Zimbabwean military forces were sent into the area. Civil society groups told of soldiers indiscriminately shooting miners and local villagers, sometimes from helicopters, in an attempt to clear the area. More than 200 people reportedly died.

A dilemma for the Kimberley Process

Marange represented a conundrum for the Kimberley Process. Despite the well documented instances of violence and other human rights violations occurring in the territory, the goods associated with the region did not meet the strict KP definition of conflict diamonds, because they were not associated with a civil war. Indeed, the forces being accused of carrying out abuses were mostly controlled by the country’s recognized government.

But the KP was not apathetic to what was happening in Zimbabwe. Although a limited KP review visit in 2007 had indicated that the country had sufficiently implemented KPCS minimum requirements, the following year, the KP expressed “growing concerns” about the Marange fields and recommended additional monitoring.

In June 2009, another KP review mission to Zimbabwe reported that the country was no longer KPCS compliant, and recommended Zimbabwe be suspended until military forces were withdrawn from Marange and illegal mining and sales ended.

At the November 2009 KP Plenary in Namibia, Zimbabwe and other participants agreed on a joint plan, by which Zimbabwe would agree to a ban on diamond exports until monitors were in place and the government had demonstrated progress. The ban did not include the Rio Tinto mine which continued to export during all that time.

In 2010, a special monitor visited Zimbabwe and the Marange fields twice. At the KP Intersessional meeting in Tel Aviv, Israel, that June, the monitor reported Zimbabwe was compliant, but the vote to adopt the report’s recommendation did not achieve consensus. The KP group agreed to meet the following month in St. Peterburg, Russia, where the World Diamond Council was holding its Annual Meeting. There, the KP authorized the first two sales of rough diamonds from Marange.

On November 3, 2011, the KP’s ban on Marange diamonds was officially lifted. The decision was controversial, leading to the withdrawal of some civil society groups from organization. Certain countries imposed their own sanctions, such as the United States, and there are retailers that avoid purchasing diamonds sourced in Zimbabwe to this very day.

Boaz Hirch (left), KP Chair in 2010, consulting with Susan Page, Assistant U.S. Deputy Secretary of State, during the special meeting of the KP that was held during the WDC Annual General Meeting in July 2010, to address the ongoing crisis in Marange.

Years of wasted revenues

A primary factor in the ongoing failure of Marange to meet its potential was the involvement of the ruling regime of Robert Mugabe, many of whose members allegedly had a direct interest in the revenues being generated by the diamond deposit.

A number of private mining companies were licensed to operate in the area, in partnership with the state-owned Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation (ZMDC). The government retained a 50 percent share in diamond operations through ZMDC.

But royalty payments, which were calculated on production volume, were low, falling to $23 million in 2015, down from $84 million in 2014. Tax payments were said to be negligible. Cited as likely reasons were production volumes being under-reported, tax avoidance and diamond smuggling. Investigative journalists reported that up to $1 billion worth of diamond revenues had been paid in kickbacks to political and military leaders, some of which were used to rig the presidential election in 2013, when Robert Mugabe claimed to have won 61 percent of the votes.

In 2016, Mugabe’s government canceled the licenses of all diamond-mining companies in the Marange diamond fields, and established the Zimbabwe Consolidated Diamond Company (ZCDC), by merging and nationalizing the assets of DTZ-OZGEO, Marange Resources, Kusena Diamonds, Diamond Mining Company and Gye Nyame. This followed a decision in March 2015 to consolidate all the diamond mining companies in the Marange region into a wholly owned government corporation.

The only diamond mine in the country to remain independently operated was Murowa. Rio Tinto sold its majority share in the facility to its former local unit RioZim in 2015. The mine changed its name to RZM Murowa in 2019.

A change in government and industry structure

In November 2017, amidst public demonstrations, a vote of no confidence and the start impeachment proceedings, the 37-year rule of Robert Mugabe came to end. A former Vice President and Minister of Defense Emmerson D. Mnangagwa was sworn in to serve the remainder of the term, and he was elected president in his own right in July 2018.

While the new government did not reverse the Mugabe regime’s decision to consolidate state assets in ZCDC, it was clear that a change in mining policy was required to enable the diamond sector meet its proper potential. In 2018, Mines Minister Winston Chitando announced that the sector would be expanded to four companies, which would be allowed to undertake exploration and mining operations. Any company or person with title for diamonds would be required for forge an alliance with one of them.

“Four is a number which was felt that it would give government and all stakeholders the effective monitoring of what is happening on the ground,” Chitando stated.

The change in policy was cautiously greeted by civil society. “With mass unemployment, high-priced basic goods and dwindling cash supplies, Zimbabwe simply cannot afford to miss out any further on the fruits of its plentiful mineral wealth,” wrote Sophia Pickles in 2019, in blog published by Global Witness.

Emmerson D. Mnangagwa, who took over as President of Zimbabee from Robert Mugabe in November 2017 and was elected in his own right the following year.

Four mining and prospecting companies

ZCDC is the largest of the four companies now operating the Zimbabwe diamond mining sector. Described as a private firm, it is nonetheless 100-percent owned by Defold Mine (Pvt) Ltd., which is a government-controlled corporation. It currently has operations in the Chiadzwa area and in nearby Chimanimani. It is also conducting extensive exploration and evaluation across the country in search of primary kimberlite pipes.

The second company is Anjin Investments, which is a jointly owned venture involving Matt Bronze Enterprises, a special purpose vehicle owned by the Zimbabwean army, and the Chinese investor Anhui Foreign Economic Construction Company. It actually had held a concession in Marange before being evicted by Mugabe’s government in 2016.

There was concern voiced about Matt Bronze Enterprises’ role in Anjin, because it signaled the military’s return to Marange. But this was played down by the Zimbabwean Mines Minster. “Anjin’s license has nothing to do with who they are and what they have done before… The fact is they will be mining our diamonds and there will be a board to oversee the operations of all companies involved in Marange,” Chitando said in July 2019.

Diamond mining operations at RZM Murowa, in the south of Zimbabwe.

The third company is Alrosa (Zimbabwe) Ltd., which was established by the Russian diamond mining company ALROSA in December 2018. In July 2019, it entered into a joint venture with ZCDC, holding a 70 percent share. At present its activities are limited to prospecting, mainly in the the Chimanimani region of Zimbabwe, and not in Marange. The joint venture agreement would provide ALROSA with a 70 percent share in any new greenfield deposits.

The fourth company is RZM Murowa, which is today a 24-hour open pit mining operation in the south of the country, with a capacity is around 1.2 million carats per annum of predominantly white, gem-quality diamonds, including reasonable quantities of large “special” stones.

Relative stability in the Zimbabwe diamond sector

The diamond mining sector in Zimbabwe today is a far cry from the chaotic and dangerous state that it was in the latter years of the Mugabe regime.

The current government expects diamonds to eventually contribute at least $1 billion to its goal of extracting minerals worth $12 billion dollars per annum, which is part of an ambitious plan to transform the country into an upper-middle-income economy by 2030. Right now, it’s only halfway there. In 2021, Zimbabwe’s mineral exports totaled $5.7 billion dollars, but that was significantly up from the $3.2 billion dollars reported in 2020.

According to the Kimberley Process, in 2021, Zimbabwe’s rough diamond exports totaled 4.23 million carats, worth $670 million. This ranked the country in seventh place worldwide in terms of both volume and U.S dollar value.

ZCDC, the country’s largest diamond miner, forecasts production of more than 5 million carats this year, up from 4.1 million carats in 2021. Its production had stood at 1.8 million carats in 2017.

Anjin Investment experienced a disappointing year in 2021, with the company recording only 70,000 carats of production, down from 790,000 carats a year earlier. This, it said, was due to the relocation of its processing plants. It projected a production ramp-up in 2022.

Diamond output at RTZ Murowa fell 28 percent in 2021 to 414,000 carats, with the dip in production attributed largely to the processing of material from low grade stockpiles, and limited mining from the operation’s K2 pit.

Reports of human rights violations are considerably less frequent today in the diamond sector, but still persist. Most often, they concern issues of unfair labor practices, and tense relations with local communities, largely because of the sometimes-violent behavior of security staff controlling the movement of residents living in and around the mining areas.

At the same time, the mining companies are conscious of how they are being portrayed in foreign markets and are more inclined than ever before to initiate and participate in projects that promote sustainability and community development. ZCDC issued a 29-page ESG report this year, and RTZ Murowa issued sustainable development reports from 2018 through 2020.

Zimbabwean mining companies are supposed allocate 5 percent of income to community share ownership trusts, although the degree to which this is realized is not clear. The Zimbabwean government has reserved a diamond concession for the Marange community, which ZCDC will mine on its behalf and allocate to the community 30 percent of net income.

There is also a greater readiness to comply with international standards. ZCDC has expressed willingness to have its mining operation independently audited against the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA) standard. This would include a desk review and onsite visits, as well as stakeholder engagement in the verification process.

RZM Murowa is both a member of the Responsible Jewellery Council, against whose standard it has been audited, and the Natural Diamond Council. Before its major shareholder, ALROSA, suspended its membership in RJC as a result of the war in Ukraine, Alrosa (Zimbabwe) Ltd. was also subject to the demands of the RJC standard.

The incoming Chair of the Kimberley Process

The consensus decision by the KP Plenary in November 2021 that Zimbabwe would serve as KP Vice Chair in 2022, and automatically assume the position of KP Chair in 2023, raised some eyebrows, but it was strongly supported by other countries in the African bloc.

Harare, the capital of Zimbabwe, which will chair the Kimberley Process in 2023 and be the seat of the KP Secretariat. (Photo credit: Tatenda Mapigoti on Unsplash.com)

The news was cautiously welcomed by leading members of the country’s civil society community as well.

“This is an opportunity for Zimbabwe to clean up its act,” said Farai Maguwu, Director of the Center for Natural Resource Governance (CNRG), speaking to Foreign Policy magazine. “There cannot be any semblance of injustice towards workers, communities, or the environment when the whole world is looking at Zimbabwe.”

A similar attitude was expressed by Shamiso Mtisi, the former Coordinator of the Civil Society Coalition in the KP and the Deputy Director of the Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association (ZELA). “A country cannot violate the KP in the same year it holds an important position,” he told Foreign Policy. “There is a lot of scrutiny, so this is the time for Zimbabwe to reform its way of doing things.”

In private conversations with WDC officials, Zimbabwean civil society representatives have reported a marked decrease in human rights violation in the country’s diamond regions, since the 2021 KP Plenary.

The Kimberley Process is not the only body in which Zimbabwe has assumed a leadership role. It currently is Vice Chair of the African Diamond Producers Association (ADPA) and in 2023, will succeed Tanzania as ADPA Chair.