A work in progress:

The Review and Reform of the KPCS

By Steven Benson,

WDC Communications

Early in the afternoon of November 4, 2022, in the main hall of the conference center hosting the Plenary Meeting of the Kimberley Process in Gaborone, Botswana, an Administrative Decision was greenlighted. It set in motion the Review and Reform Process that will occupy the organization’s attention over the coming year and beyond.

The brief AD dealt with the establishment of an ad hoc committee that will be charged with overseeing the Review and Reform Process, and briefly listed key issues that it will need to address. Foremost among them was the definition of conflict diamonds in the Kimberley Process Core Document. Other subjects included the strengthening of KP governance, defining what constitutes Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS) compliance in producing countries, technical assistance provided by KP Participants, and alternatives for broadening the number of countries that may eventually consider becoming candidates for KP Vice Chair.

Hours later, during the marathon session that ended with the approval of the Plenary’s Final Communiqué, it was agreed that the new Review and Reform Ad Hoc Committee would be chaired by Angola and the Vice Chair would be South Africa.

The work of the new body is scheduled to begin at the start of 2023.

The 2022 KP Plenary in session in Gaborone, Botswana, on November 5. Angola, whose delegation is seen in the foreground, was appointed at the Chair of the Ad Hoc Committee on Review and Reform.

KPCS should be subject to periodic review

While the committee overseeing the Review and Reform Process is ad hoc and is not one of the KP’s permanent working groups, the process itself is a fixture in the KP’s working schedule.

Article 20 of the KP Core Document refers to a Review Mechanism, specifically stating that “the Certification Scheme should be subject to periodic review, to allow Participants to conduct a thorough analysis of all elements contained in the scheme.”

Indeed, according to the Core Document, not only should the Review Mechanism consider reforming the KPCS, it also should “include consideration of the continuing requirement for such a scheme, in view of the perception of the Participants, and of international organizations, in particular the United Nations, of the continued threat posed at that time by conflict diamonds.”

According to the Core Document, the first review was to take place no later than three years after the effective starting date of the KPCS, which would be in January 2006.

The Core Document did not specifically refer to the frequency at which reviews should occur, but it was later decided that a reform cycle would begin every five years. The length of each would depend on the subjects under review and be subject to approval by the Plenary.

The explicit reference to a Review and Reform Process in the Core Document was of particular significance, because its represented recognition from the very beginning that the KPCS is a work in progress, and it would need to adapt and evolve according to current conditions. These were expected to change over the course of time.

It is important to note that the Review and Reform Process is a means to an end, but not an end unto itself. While the ad hoc committees that have been created during the 20 years that the KPCS has been in operation have investigated, discussed and suggested proposals for reform, all have been subservient to the regular decision-making process in the KP. They thus essentially have been advisory bodies, with any amendment to the KP Core Document or an administrative decision ultimately requiring approval by the Plenary, where it is necessary to obtain the consensus of the governments of all KP member countries – or regions, as in the case of the European Union.

Historically, when it comes to reform, the organization has shown itself to be more inclined, or at the very least more able, to amend existing administrative processes and structures, or create new ones. But it has proven decidedly less capable of changing elements of the KP’s core mission. Thus, while the KP almost certainly operates more efficiently and effectively than it did 20 years ago as a result of the Review Mechanism, the scope of its purview is essentially the same as it was when the KPCS was launched in 2003.

The ad hoc committee that oversaw the previous KP Review and Reform Process, meeting in Paris, France, on April 20, 2018.

Previous review produces mixed results

The most recent Review and Reform Process, which ended in 2019, illustrates this reality quite accurately. It was coordinated by an Ad Hoc Committee on Review and Reform established at the 2017 KP Plenary Meeting in Brisbane, Australia, which also was chaired by Angola, with Canada serving as the vice chair.

The committee was charged with considering a number of topics, among them changes to the KPCS Core Document, with one of them being the scope of the conflict diamonds definition; improvements to the Peer Review Mechanism; the establishment of a Multi-Donor Fund to assist the involvement in the KP of less economically capable countries and civil society; and the establishment of the Permanent KP Secretariat.

A series of sub-teams were created to deal with each individually. The WDC came to chair the one considering a Permanent KP Secretariat and participated in all others.

When the Review and Reform cycle that began in Brisbane concluded at the 2019 KP Plenary meeting in New Delhi, India, the results were mixed.

On the plus side, the Plenary adopted an Administrative Decision on a Peer Review Mechanism recommended by the relevant sub-team, which aimed to improve the provisions of peer review including annual reporting, review visits and review missions.

Also successful was the work of the sub-team chaired by WDC on the establishment of a Permanent KP Secretariat. As a result of its efforts, the 2019 Plenary endorsed the creation of a Technical Expert Team (TET) under the Working Group of Diamond Experts (WGDE), also chaired by WDC, to make an evaluation of the candidates to host the Permanent KP Secretariat, in line with the evaluation criteria that had developed by the sub-team. That process eventually bore fruit at the most recent KP Plenary meeting, held in Gaborone in November 2022, where Botswana was ratified at the site of the Permanent KP Secretariat, starting in 2024.

The efforts of the sub-team working on a Multi-Donor Fund were inconclusive at best. While the 2019 Plenary noted its agreement that the KP could benefit from the establishment of such a funding mechanism, and also confirmed priority areas that it could focus upon – namely capacity building, technical assistance, the participation of civil society and least developed countries – it delayed making a decision, implying that this should be deferred until a Permanent KP Secretariat has been created.

But the real impasse came with proposed amending of the KP Core Document. While the Review and Reform sub-team did manage to find agreement on a number of non-controversial clauses, by consolidating the document with all the AD’s published over the years, agreement could not be reached on revising the conflict diamond definition. That would have had the effect of broadening the scope of KP’s mission.

The 2019 KP Plenary’s Final Communiqué tersely stated “no consensus could be found on an updated conflict diamond definition.”

Definition proves to be the toughest hurdle

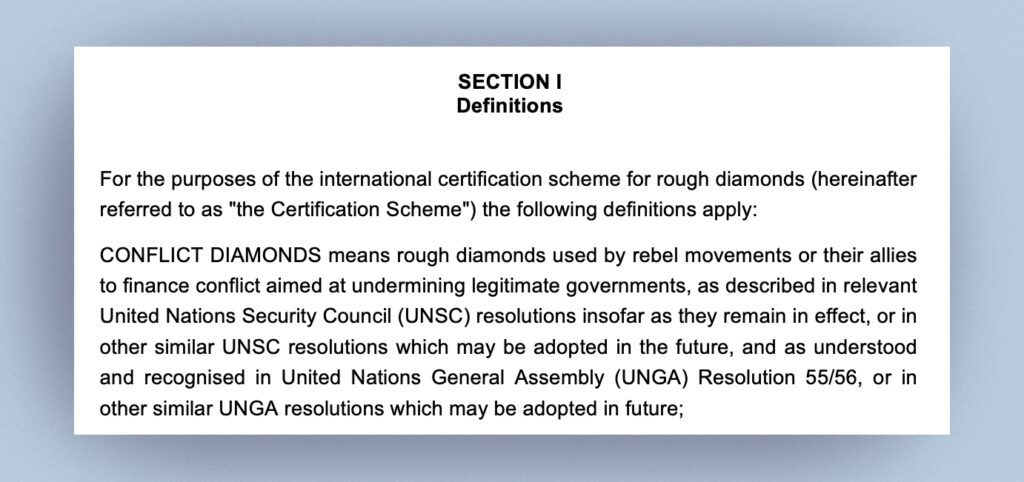

The possibility of amending the conflict diamonds definition has been discussed for more than a decade already, with proponents of such a move arguing that the prevailing text, which remains unchanged since the Core Document was first ratified in 2002, is no longer relevant. It limits conflict diamonds to be “rough diamonds used by rebel movements or their allies to finance conflict aimed at undermining legitimate governments,” and does not include goods directly associated with other violations of human rights.

“The world is markedly different today, as are the challenges and threats that confront us, but the definition has remained the same – it’s no longer acceptable,” stated WDC President Edward Asscher in his address to the Opening Session of 2022 KP Plenary on November 1. “We have fallen short when we attempted to [amend it], most recently in New Delhi in 2019.”

The conflict diamond definition, as it was formulated in 2002, and still is valid in 2022.

“We were unable to reach consensus in the previous Review and Reform cycle about how it may be possible to reference violations of human rights in the conflict diamonds definition,” Mr. Asscher continued. “But in the past two years the centrality of human rights has been formally recognized by the KP Plenary.”

The WDC President was referring to Frame 7, which had been ratified in a declaration at the 2021 KP Plenary in Moscow, defining the key requirements for responsibly sourcing rough diamonds in the supply chain. It specifically cited the protection of human rights and labor rights, along with community building, the protection of the environment, anti-money laundering, anti-corruption and differentiating between natural diamonds and synthetics.

‘The upcoming Review and Reform cycle must succeed or KP will risk becoming irrelevant,” Mr. Asscher told the Plenary.

Review and Reform does not start from scratch

The new Review and Reform cycle will simultaneously begin with the handover of the office of KP Chair from Botswana to Zimbabwe. Its first order of business will be defining the sub-teams that will work on each of the designated topics under discussion.

The duration of the Review and Reform Cycle has not yet been set, although at a meeting in Dubai in October, which preceded the 2022 KP Plenary and was held specifically to discuss the Administrative Decision to set up and create parameters for new Review and Reform Ad Hoc Committee, there were calls that its work be fast-tracked, and that results be achieved within a year at the 2023 Plenary meeting in Zimbabwe.

That may be an overly optimistic expectation, but it will be up to the 2023 KP Plenary to decide whether the cycle should be extended.

In any case, as far as the conflict diamond definition is concerned, the sub-team that deals with the Core Document within the KP’s Committee on Rules and Procedures (CRP) has agreed that the work of the Review and Reform Ad Hoc Committee will not begin from scratch, but rather from the point at which work was suspended during the 2019 KP Plenary meeting. This is significant because, for a while during its final session in New Delhi, the Kimberley Process seemed to be tantalizingly close to achieving consensus on the definition. But then a single objection prevented this from becoming reality.

After the 2022 Plenary approved a Final Communiqué, the WDC President struck an optimistic tone. “While we appreciate it is early days yet, we all are most gratified that there is broad agreement that the updating of the conflict diamond definition will be a key task of the new committee,” Mr. Asscher said. “I have spoken at length about the shortcomings of the existing definition, and the degree to which it threatens to render the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme as irrelevant among diamond consumers. I do not expect the coming debate to be easy, but it is an area in which failure is not an option. I felt here that all countries present accept the need for change.”