I am an African,

and a new kind of diplomat

WDC Kimberley Process Task Force member Kele Mafole, who is the International Relations Lead for De Beers Group.

The New Generation is a WDC News Update series that tells the stories of up-and-coming diamond industry leaders, examining the role that they see for themselves, in the business and the diamond itself. Each article in the series is delivered in the person’s own voice.

The fourth article in the series features Kele Mafole, International Relations Lead for De Beers Group and member of the WDC’s Kimberley Process Task Force.

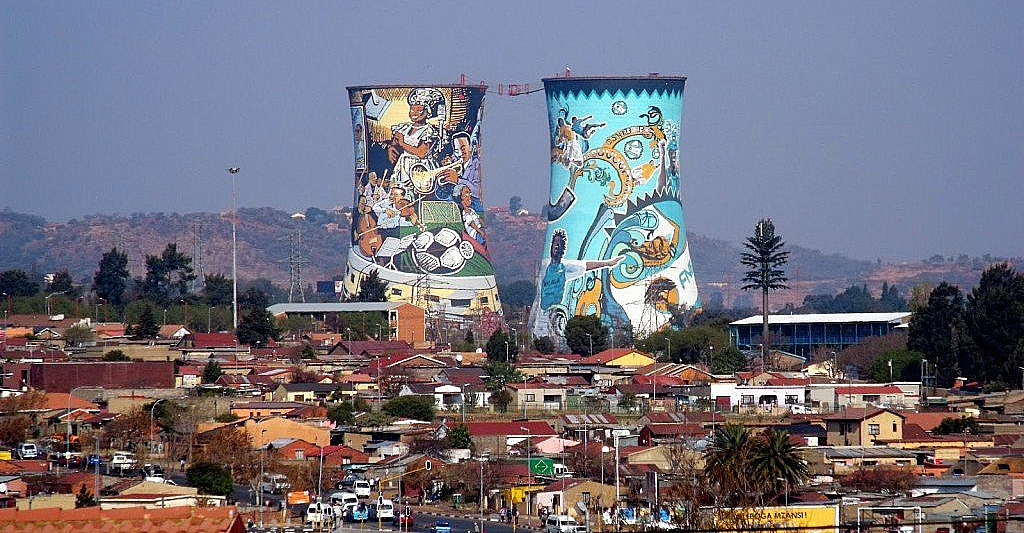

Although I may not have been fully conscious of it, as a small child mines and mining were always a feature of my landscape. My horizon was dotted with what I naïvely thought were mountains, but I was to find out that they were abandoned mines – a remnant of the old days of gold mining in my hometown.

My name is Kele Mafole. I am the International Relations Lead for De Beers Group. I am based in London, but I was born and grew up in the City of Gold, Johannesburg.

As a young adult, even though I was surrounded by the mines and knew the history of my city and its connection to the mining boom of the 19th Century, the idea of working in the industry never seemed a possibility and, indeed, was somewhat unattractive to me.

First, every August the winds would rip across Soweto, my neighbourhood, and it would be covered in a cloud of very fine, golden-white dust that would settle on every surface and which, despite all our efforts, always ended up in our eyes and mouths. Second, the imagery of mining evoked connotations of hard and dangerous labor reserved mainly for hardened Black men.

Most importantly, for me mining represented oppression, the legacy of apartheid and the inhuman treatment of Black people by the then government of South Africa.

Soweto, the massive urban township in the southwest of Johannesburg, where Kele Mafole grew up. Originally designated as area where Black South Africans could live, in the 1960 and 1970s it became the center of resistance that eventually led to the fall of the country’s apartheid regime.

That I am working in the mining industry, for the leading diamond company in the world, is a wonder to me – even now, more than one year in the game. My journey to this point was not a straightforward path.

Member of the ‘Born Free’ generation

It all started one morning on my way to high school, when I heard a short clip of former South African President Thabo Mbeki’s “I am an African” speech on the radio.

Something happened within me. I experienced an indescribable feeling of responsibility, and I knew immediately that, one way or another, I was going to work in the service of the ideals he had expressed. This is because I am indeed an African. And, as a product of South Africa’s liberation struggle, I would not waste the access I had to opportunities that were never open to my parents, their parents or their parents’ parents.

I am part of the “Born Free” generation of South Africa’s “Rainbow Nation.” I was among the first of my compatriots to attend a multi-racial school and enjoy the freedoms of a non-racial, democratic South Africa.

After high school, I enrolled to study politics and Economics at Wits University in Johannesburg, and went on to major in economics and international relations.

After graduating in 2008, at the start of the global financial crisis, I found myself unemployed for almost three years. It was a hard reckoning – both depressing and humbling to learn that no matter my potential, the hard work I had put in, and the financial investment my mom had made, I was not immune from the high unemployment rate that continues to plague my country and is a barrier to young South Africans.

But I understood that I was responsible for my own future and that I had to find and pursue every lead to change my life. During that time, the “I am an African” poem continued to motivate and give me hope. It continues to shape my identity to this very day.

A schooling in diplomacy

In 2011, I was among the 39 cadets to be selected from among 2,500 applicants to join the coveted Diplomatic Cadet Programme of the South African Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

It was a highly competitive, gruelling arena where, as cadets, we learned to function in a pressurised environment that demanded the best of us, academically and emotionally.

After graduating from the programme in 2012, I was permanently placed at the Economic Development Desk in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Multilateral Branch.

I spent almost a decade working within the ministry, and for much of that time I was actively involved in the United Nations’ transition from the Millennium Development Goals to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the SDGs.

The author, speaking at the United Nations, as a representative of South Africa’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Kele Mafole as a South African delegate at the Kimberley Process Intersessional meeting in Angola in June 2015.

I was later deployed to represent South Africa within the Kimberley Process and so it was in the foreign policy space that I was exposed to diamonds and the political dynamics that regulate the trade.

The Kimberley Process became a very big part of my work and I fell in love with the initiative and what we are trying to achieve through it.

In the foreign and diplomatic service, I worked under the guidance of nurturing managers, who helped shape my voice and passion for multilateral negotiation. Representing my country at the United Nations in New York and Geneva was a dream, although it was hard to ignore that I was a young woman in a man’s world. Other than my colleagues and friends at Head Office, there were very few young, Black people in the meetings I attended.

There were, however, some outstanding women that I admired, like Amina J. Mohammed, Ambassador Nozipho Diseko and Nardos Bekele-Thomas. These women were the epitome of grace and integrity. They exuded power and a feminine strength that I was deeply attracted to. I wanted to be them. As I contemplated what I wanted to do and who I wanted to be, my view turned global, and I knew that I would need to leave South Africa to pursue that future.

If you will it, it is no dream

Someone once said to me, “if you will it, it is no dream”. And so I went to work on realising my vision.

I planned to get a Master’s degree from a prestigious international university, and then get a permanent job within the UN Secretariat, and rise through the ranks of the UN system, doing important work that contributed to a better world.

And so, in 2018, I was awarded a scholarship to study risk management and futures at the London School of Economics and Political Science. But, while there, something shifted, and I no longer dreamed of New York.

In 2020, during the pandemic, I followed my heart, took the boldest risk of my life and I moved permanently to London.

It took me a full year of countless interviews for many different roles before I finally found my current job at De Beers Group in 2021. I feel fortunate, because I am again surrounded by strong women – my managers and mentors, Purvi Shah and Feriel Zerouki, and my friends like WDC Executive Director Elodie Daguzan, who inspire me and who in the short time I have been here, have pushed me to greater heights.

Changing seats at the negotiating table

Since I became a member of the Kimberley Process Task Force (KPTF) the same year I joined De Beers, I have had the privilege of representing and defending the interests of the diverse constituents of the global diamond industry, to promote consumer confidence in natural diamonds.

Although I had negotiated opposing positions to the diamond industry at the KP early in my diplomatic career, I have come to learn and appreciate the real value that natural diamonds bring to the people that work across its value chain, the host countries, communities and consumers. I hold a new and refreshing view of diamonds and I am proud to work in service of these ideals.

The WDC’s KP Task Force is a solutions-oriented community of thinkers who debate and work hard to understand the potential risks and manage the impacts of the industry on people and the environment. We are a group that shares ideas to bridge a broad understanding of our common ambitions in creative ways, bringing all stakeholders together. It is about relationships and trust. And as I continuously learn from Feriel, trust is our most valuable asset.

After joining the private sector, the author, now employed by De Beers, examining diamonds at the DMCC in Dubai.

Members of of the WDC’s Kimberley Process Task Force during plane trip, while visiting Zimbabwe in November 2022, from left: Kele Mafole, WDC Executive Director Elodie Daguzan, WDC President Edward Asscher, and fellow KP Task Force member Alexander Gul.

I look back on my life and the course of my career and I can’t help but be grateful. My family still lives in Soweto – the township once built to control the movement of Black people in Johannesburg, which is today, the vibrant urban hub of the city. When I go home, I am often overcome by conflicting feelings of immense pride in where I come from and what I have been able to achieve on the world stage, alongside sadness at the state of poverty that others have not been able to escape. I believe that this duality – my Black African township experience, which coexists harmoniously with my experiences in the diamond and luxury industry – is my strength and also colors my perspective and contribution to the WDC.

Having taken the huge risk of changing my career path at the height of the pandemic, I am happy that the diamond industry is my home, where my perspective is valued and my opinion matters.

I am a new kind of diplomat for a dynamic and exciting diamond industry. My role and purpose are aligned to the aspirations that have driven my life choices from the very beginning.

My name is Kele Mafole and I am an African.