WHY KIMBERLEY PROCESS CERTIFICATES LACK

A STANDARD FORMAT AND LAYOUT

By Mark Van Bockstael

Chair, KP Working Group of Diamond Experts

Chairman, WDC Technical Committee

It must be one of the most frequently encountered questions about the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS) – Why is there no single standard shape or form to a Kimberley Process certificate?

Indeed, each and every KP country – or “KP Participant” in KP-speak – issues certificates that look and feel different to those of its neighbors. Over the years, diamond traders, forwarders, customs agents and law enforcement professionals have complained about the lack of standardization, and how it impacts on them doing their job. For one thing, they say, it makes looking out for counterfeits more complicated than it should be.

This was not due to any oversight or administrative mix-up. It was the result of how the Kimberley Process came together and how some old ghosts from the past still haunt us.

As is well documented, the KP was launched in May 2000 to discuss how a worldwide rough diamond certification system could break the link between diamonds and conflict in Africa.

It was realized at the time that the rebel forces plundering the diamond fields may be able to evade the UN sanctions on rough diamond exports from certain afflicted countries, by falsely claiming that the stones they held had originated in a non-sanctioned nation.

Such a problem, the KP founders believed, could be countered by having government-controlled authorities in rough diamond-producing countries issue certificates for all legal output in their own territories. Since conflict diamonds held by rebels would not be able to receive bona fide certification, they would be removed from the legitimate diamond pipeline.

UN Resolutions and Certificates of Origin

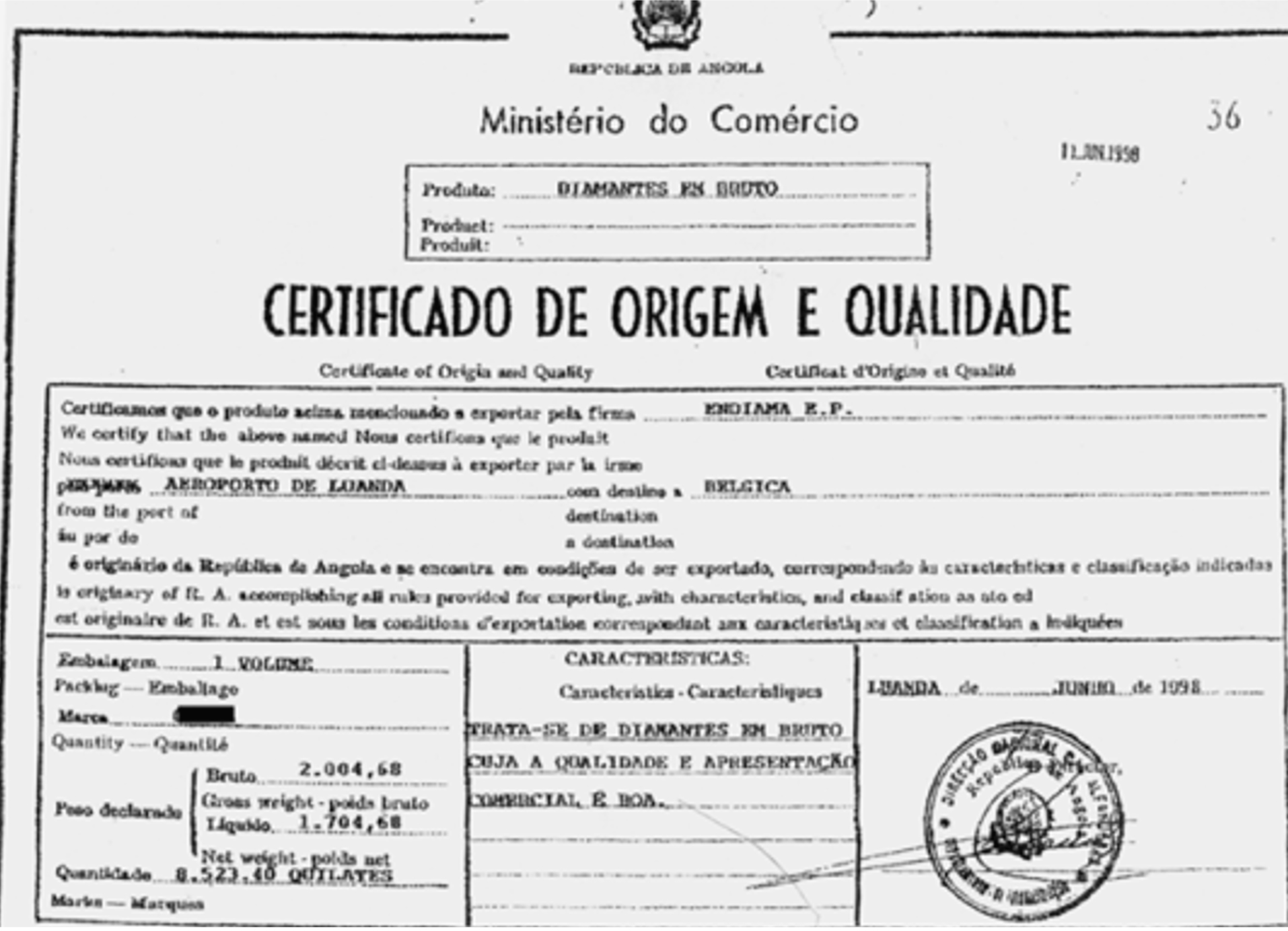

Government-issued certificates for rough diamond shipments actually precede the Kimberley Process. The very first embargo associated with conflict diamonds was approved by the United Nations Security Council in June 1998, and involved stones being traded by rebels in Angola. It ruled that the only rough diamonds eligible for export from the country were those carrying an official Certificate of Origin issued by the Angolan government, verifying that they were sourced in areas under its control.

Two years later, a second UN Security Council rough diamond embargo was approved, this time covering goods traded by rebel forces in Sierra Leone. The resolution essentially copy-pasted the wording used in the first embargo, this time referring to a Sierra Leonean Certificate of Origin.

By mid-2002, six months before the launch of the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme at the start of the following year, the governments of four diamond-producing countries were issuing Certificates of Origin with each legal shipment of rough diamonds – Angola, Sierra Leone, Guinea and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). This was being done in accordance with UN Security Council resolutions, or as follow-up to recommendations from the relevant UN Panel of Experts.

Certificates Transformed, from Low-Tech to High-Tech

The first Certificate of Origin issued by the Angolan government wasn’t much more than a simple black-and-white photocopied form, without any security features. It was easy to forge and not really a conflict diamond-stopper.

In January 1999, Canada’s Ambassador to the United Nations, Robert Fowler, was appointed Chairman of the Sanctions Committee on UNITA, the Angolan rebel movement. He was sharply critical of the overly simple certificates that had been issued to that point, and in September the Angolan government, together with Belgium’s Diamond High Council, or HRD (the forerunner of the AWDC, or Antwerp World Diamond Center), had begun work on a tamper-proof Angolan Certificate of Origin. It was ready for use by December.

Three months after UN Security Council Resolution 1306 was passed in July 2000, requiring Certificates of Origin for all legal exports of conflict-free diamonds from Sierra Leone, a tamper-resistant Certificate of Origin from that country was also unveiled. In addition to an array of physical security features, it also included an “Import Confirmation,” which required the authorities in the importing country to confirm receipt of the merchandise, listing details such as certificate number, weight and value.

The Sierra Leone Certificate of Origin was also the first one where the paper copy was complemented by a digital version, with end-to-end encryption. It involved technology that today, 20 years later, is standardly used by many digital messaging platforms.

The Sierra Leonean document and its digital avatar were thoroughly examined for security flaws by the U.S. Secret Service, which reported on it during the White House Diamond Conference on January 11, 2001. It passed with flying colors. Never before had this level of security been attempted, nor has been surpassed or even matched ever since.

A Proliferation of KP Certificates

From 2000 to 2002, during the negotiation process leading up to the launch of the KPCS, a variety of different certificate formats were created. In addition to the versions created by the governments of Angola and Sierra Leone, others were developed by the governments of Guinea and the DRC, based on the Sierra Leone template.

The first Angolan Certificate of Origin, issued in 1998, did not have any security features at all.

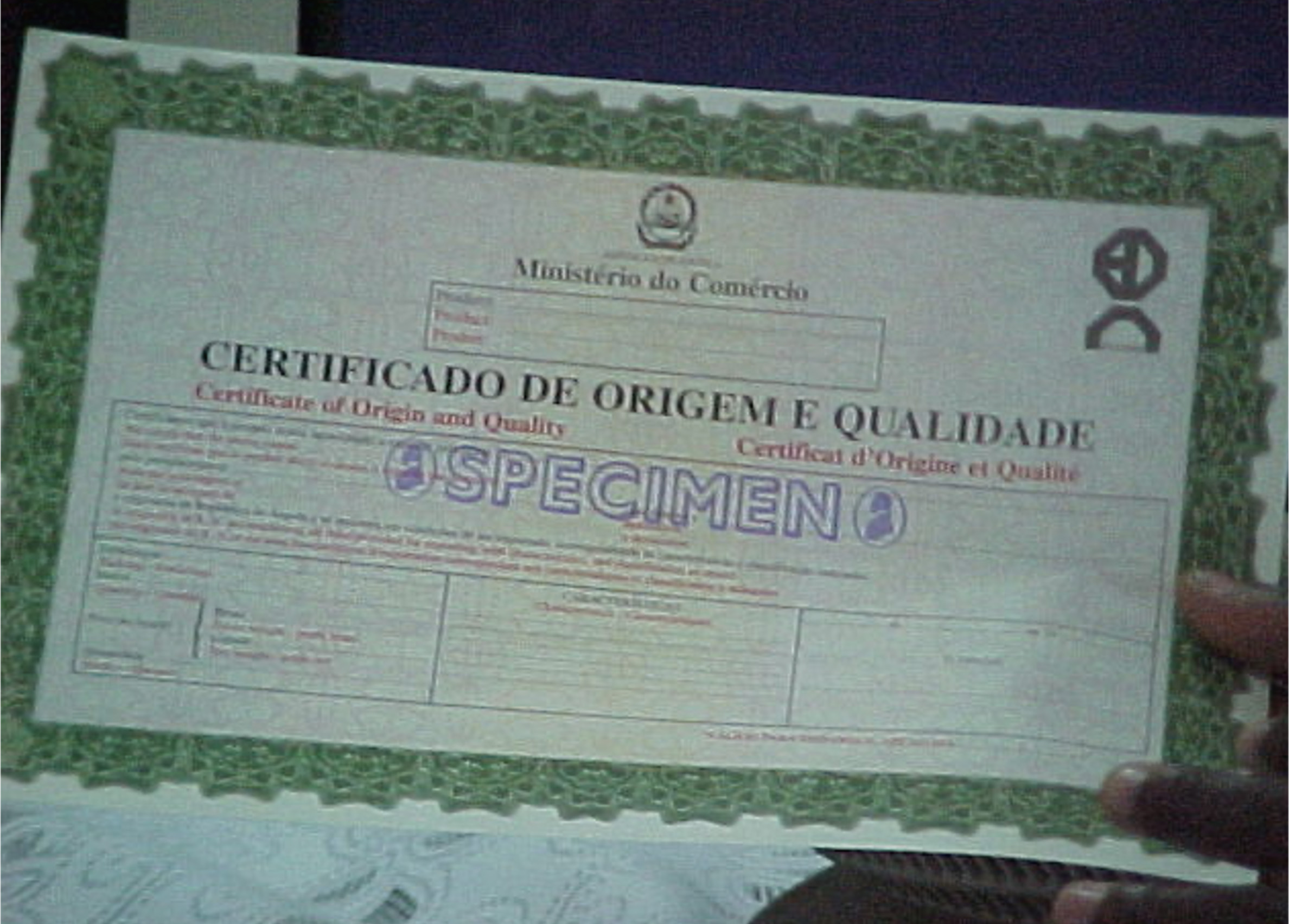

The improved design of Angola’s Certificate of Origin, developed by the country’s government with the support of Belgium’s HRD, released for use in December 1999.

The sophisticated Sierra Leone Certificate of Origin, released in October 2000, served as model for the certificates of origin of Guinea and the DRC. It was also proposed as a template during the KP negotiation process.

The number of formats increased with the impending launch of the certification scheme in 2003. They included a certificate by the South Africans, which became a model for other states in the Southern African Development Community (SADC). Australia, Russia, Canada and a number of smaller African diamond producers also designed their own certificates, each with its own specific format.

The lack of uniformity could actually be traced to Resolution 55/56, passed by the UN General Assembly in 2000, which provided the mandate for the Kimberley Process and found its way in the Preamble of the KPCS core document. It was deliberately vague, stating simply that “the international community develop detailed proposals for a simple and workable international certification scheme for rough diamonds based primarily on national certification schemes and on internationally agreed minimum standards…”

The UN resolution did not spell out how the various members of the certification scheme – the KP Participants – may coordinate their systems with one another, and certainly did not prescribe homogenous certificate formats.

The Rise and Demise of Certificates of Origin

With the launch of the certification, things became more complicated. The KPCS required every Participant country to issue certificates for conflict-free rough diamonds exported from their territory. These documents were not necessarily certificates of origin.

Up until then only diamond-mining countries had been issuing certificates. Nations like Belgium, Israel, India, China and the United States, all of which register sizeable rough diamond exports but are essentially through stations, would now be required to produce their own documentation, although in the case of Belgium it would be done by the European Union.

In the early days of the negotiation period, a suggestion was made that non-diamond mining countries issue a “Certificate of Legitimacy.” That proposal remained on the table until, finally, the KP Plenary decided that all conflict-free diamond shipments must be treated equally and be issued the same type of accompanying document. A Kimberley Process Certificate, therefore, is not a Certificate of Origin by definition.

During the last negotiation meeting in Ottawa in early 2002, a last-ditch effort was made to bring some commonality to format and layout – the look-and-feel – of Kimberley Process Certificates. Unfortunately, it was eclipsed by a byzantine discussion on proposals for the KP logo that was supposed to appear on all documents.

THE CERTIFICATE OF ORIGIN

A Certificate of Origin is document that certifies that the merchandise contained in a particular export shipment was wholly acquired, produced, manufactured or processed in a specific country. In other words, it assigns a “nationality” to a product. It also serves as a declaration by the exporter to meet customs and/or trade requirements.

Certificates of Origin were mainly issued by Chambers of Commerce to accompany shipments of certain goods produced in a particular country.

But the requirement in the UN Security Council’s resolutions that diamond shipments be accompanied by Certificates of Origin issued by state-sanctioned authorities forced governments to begin issuing Certificate of Origin themselves, thereby superseding the role traditionally played by chambers of commerce in their countries.

THE CURIOUSLY ABSENT KP LOGO

The ubiquitous Kimberley Process logo, featuring a blue impression of the earth’s continents, intended to highlight the United Nations mandate, above a rough diamond, is well known but still notably absent from KP Certificates.

Used by the KP, it was created by two Swiss customs officials, Beat Frei and P. Ackermann in 2002. Mr. Frei is seen above, alongside the KP logo he co-designed, at a function in New Delhi in 2008 during India’s tenure as KP Chair.

The logo was adopted by the KP Plenary too late for inclusion in the KP certificates at the launch of the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme in early 2003.

In fact, it took the KP another 10 years to acknowledge the logo creators’ contribution. That happened in 2013, in the Final Communiqué of the KP Plenary that year.