THE RISK INHERENT IN BLURRING THE DISTINCTION

BETWEEN ‘KIMBERLEY PROCESS’ AND

‘KIMBERLEY PROCESS CERTIFICATION SCHEME’

By Mark Van Bockstael

Chair, KP Working Group of Diamond Experts

Chairman, WDC Technical Committee

A question one frequently stumbles over when discussing the international forum and system created to eliminate the trade in conflict diamonds is whether to use the term “Kimberley Process” or the term “Kimberley Process Certification Scheme.”

To many, the two seem to be interchangeable, with both frequently and often confusingly being encountered within the same texts, as if they are synonyms. A visit to the website of the Kimberley Process doesn’t clarify much, although it does state correctly that the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS) came about as a result of the Kimberley Process (KP) negotiations that started in May 2000 in Kimberley, South Africa. From there on it becomes a little bit more confusing.

What started off as the “Technical Forum on Diamonds” in Kimberley, South Africa, 21 years ago, became known as the Kimberley Process, when the results of five meetings involving representatives of the diamond industry, civil society and interested governments were presented by South African delegates to the United Nations General Assembly. The UNGA then mandated the founding group to bring in other members and continue the discussions about delivering a system that would end the trade in rough diamonds fuelling civil conflict.

The original Technical Forum on Diamonds became the “enlarged Kimberley Process.” In November 2002, the negotiations within the now bigger group concluded with the Interlaken Declaration. That resulted in the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme, which was launched on January 1, 2003.

A parliament and the statute it legislates

So, what is the difference – if there indeed is any –between the KP and the KPCS?

All scheduled annual events, including the Intersessional meetings that are typically held between May and June and the Plenary meetings in November or December, are described as KP meetings. But few would strictly qualify as such. Most are in fact KPCS meetings, where the implementation of the certification scheme is discussed.

A KP meeting essentially involves a political discourse about the KPCS Core Document whose primary role is to outline the regulations that need to be translated into national legislation in all KP-member countries. In this forum, representatives of governments, civil society and industry are all equally entitled to voice their opinion about the wording and interpretation of the document.

But while the political discourse within the KP is egalitarian, the process of translating that discussion into decisions that affect the implementation of the KPCS is restricted. This is because the KPCS Core Document designates governments as Participants, who have decision-making authority, while it grants Observer status to the diamond industry and civil society, respectively represented by the World Diamond Council and the KP Civil Society Coalition.

There is a common-sense logic to this approach. Since the KPCS can only be enforced at the country level by authorized legal entities, such as customs and the judicial authorities, acting according to the dictates of national law, it would appear reasonable that, when it comes to implementation, the opinion of governments holds sway. As one WDC President put it, in the KP “the industry has no vote, but a clear voice.”

To draw an analogy, the KP is the parliament, whereas the KPCS is the statute it has legislated. Thus, the KP is a dynamic organism, whereas the KPCS is a static entity, and is only subject to change through actions taken by the first. According to the rules, this should occur during the three-year KPCS review process that takes place every five years or so.

Portending an existential crisis

But the once clear distinction between the Kimberley Process and its product, the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme, has become blurred.

In 2019, the most recent three-year review of the KPCS Core Document ended at the KP Plenary in Delhi, India, under a cloud of disappointment. Several important topics were not resolved – most notably the broadening of the scope of the KPCS, through the expansion of the definition of conflict diamonds.

It should be noted that, while the period originally allocated to reviewing the KPCS was over, at least until 2023 when a new three-year period would commence, the certification scheme itself remained intact, albeit not as effective as some would have liked. In other words, the inability to reach agreement was not a failure of the KPCS, but rather a failure of the KP.

But frustrated at its inability to achieve success, the KP Plenary agreed not to shelve the unresolved issues, and instead keep them on the agenda in the hope that agreement can be reached. That possibility, however, is far from certain.

The stakes are high. With the impotence inherent in the political process being conflated with the certification scheme itself, the viability of the KPCS is being undermined. This is despite the fact that, in spite of its shortcomings, the certification scheme is remarkably effective, and continues to fulfil a vital function. Indeed, it anchors the entire diamond trade.

In a worst-case scenario, muddling the distinction between KP and KPCS could portend an existential crisis. If the KP is not capable of change, the crisis of confidence in the political process could mean game over for the KPCS.

COSTS HAPPEN WHERE THEY FALL

An unintended consequence of the unusual structure of the Kimberley Process is the lack of an annual budget. This is because the KP is not actually a registered organization, but rather a forum of interested governments, members of industry and civil society, who have agreed to share information and opinions about eradicating the international trade in conflict governments, and, in the case of governments, also implementing the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme in the territories in their jurisdiction.

This does not mean that the KP does not need cash in order to operate. Quite the opposite, it requires some serious financial inputs. Organizing two physical KP meetings annually, pandemics permitting, lasting five days each for approximately 500 delegates, including simultaneous translation in five languages, is not a cheap undertaking. Nor does the KP have the funding to pay for review visits, websites and communications activities, the collection and collation of statistics, special monitoring committees and more.

So, any KP Participant country contemplating running for Vice Chair, must be prepared to underwrite much of the necessary amount, when at the end of the following year it becomes the KP Chair for a period of 12 months. Little wonder then that there are not too many candidates available.

In KP-speak, the requirement that the country holding the KP Chair must provide the funds necessary for a full working year is euphemistically called “Costs happen where they fall.” But this is not limited to the KP Chair. The chairs of all KP bodies – working groups and committees – need to provide the budget necessary to fulfil their mandate. This may explain why the rotation of chairs has remained infrequent.

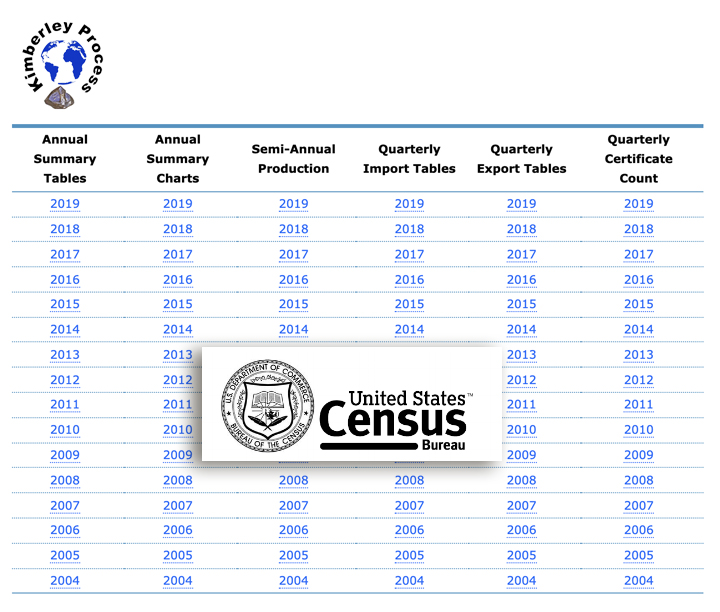

Most probably the most expensive body to run is the Working Group of Statistics (WGS). Maintaining and continuously improving the important KP Statistics website and providing technical assistance to all KP Participants (countries) is not only costly, but it requires considerable skills and experience. So, it should come as no big surprise that for a great many years the U.S. Census Bureau has chaired the Working Group on Statistics on behalf of the United States.

It’s also essential to note that the industry representative in the KP, the WDC, has reliably carried a fair portion of the financial burden, together and in support of whatever country happens to hold the KP Chair at any point in time. In addition to chairing the Working Group of Diamond Experts, since 2013 the WDC has hosted the KP’s Administrative Support Mechanism (ASM), by which the KPCS is supported via a website; the facilitating of communications to and among KP member states, observers and other stakeholders; the providing of logistical support to the KP Chair and working group and ad-hoc committee chairs in planning Intersessional, Plenary and other working meeting; support for the Working Group on Monitoring in administering the peer review system; and any other tasks as agreed by the KP Plenary or requested by the KP Chair or a working group chair.

Furthermore, the WDC has also agreed to partially finance the KP Permanent Secretariat, which it is hoped will become the organization’s administrative backbone. In this respect it is also chairing, and therefore helping to finance, the sub-committee that is planning the new body.

WHY ‘.com AND NOT ‘.org’?

Domain names on the Internet tend to end with a domain extension that tell you something about the website. They could, for example, indicate its location such as “.it,” indicating it is an entity in Italy. The most ubiquitous extension, of course, is “.com,” which certainly is the favored alternatives among businesses keen to indicate that they have a global, rather mainly local appeal.

“.org” is the extension favored international associations, foundations and other bodies that wish to show that they are not profit-driven.

Confusingly, though, the website of the Kimberley Process, which is both international and not profit-driven, has a “.com” extension (www.kimberleyprocess.com), whereas the website carrying all its statistical data is www.kimberleyprocessstatistics.org.

So why does a supposedly .org present itself as a .com. Again, it comes down to the fact that the KP is a forum rather than an organization. When the KPCS was launched on January 1, 2003, as the result of a remarkable agreement between multiple countries, industry and civil society, there was no meeting of the minds about which country would own the domain name.

The rights to www.kimberleyprocess.org were acquired by an individual from one of the negotiating teams, who has remained its legal owner ever since. Attempts to wrestle it away at no cost for use by the KP have proven unsuccessful to this very day.

Over the years the KP has appeared to come to terms with its .com extension. Be that as it may, the situation illustrates well the difficulties caused by not being a legal entity. It is incapable of owning anything, not even a website.

The result is that the KP website was passed on from 2004 from one KP Chair to the next, starting with Canada, until 2011, when the DRC was in control. But that year it crashed, and it was deemed to be beyond repair.

The Chair from the DRC requested that the Antwerp World Diamond Centre (AWDC), a WDC member, provide emergency relief, until such time that the incoming KP Chair, the United States, could build a more functional and robust website. Restoring the lost data and then developing the new KP website took a chunky bite out of the Belgian organization’s IT budget.

Since 2013, the task of maintaining and updating the KP website has been a job of the Administrative Support Mechanism (ASM), which is a managed by the WDC. But in effect it is AWDC that has continued to fulfil the function, as part of its role as “ASM focal point.”

The last major update of the KP website, including a revamped look-and-feel, was prepared and paid for by the Dubai Multi Commodities Centre (DMCC) during UAE’s tenure as KP Chair in 2016.

Currently, talks are underway on establishing a Permanent KP Secretariat, taking over all functions of the ASM and more. This time , hopefully, it will be a legal entity, complete with a working annual budget.